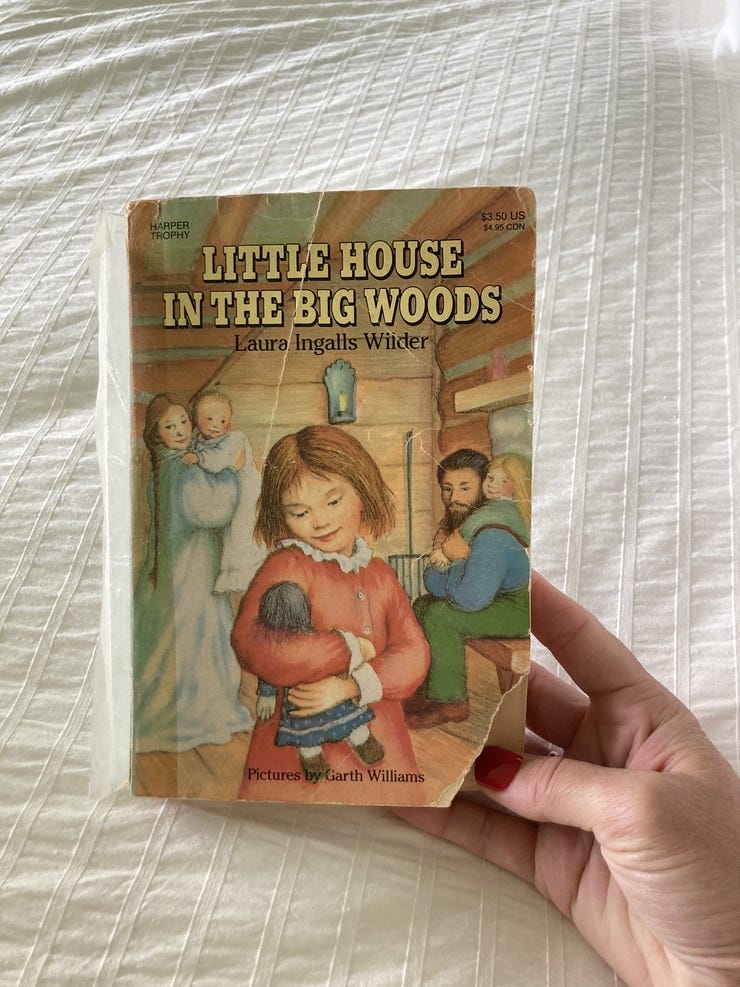

At this point in American history, if you lived outside of a town, life was very good but also hard and dangerous. Your food supply was your problem, and your problem alone. You either grew it, raised it, or hunted it. Then you had to preserve it and enough of it to keep you through the winter. If you were lazy or didn't think through what you needed in twelve months and failed to prepare, you and your family died. The government wasn't around the corner in another log cabin to give you food stamps or anything else. Family and friends helped, but they lived hours away. There wasn't much of a social safety net. One small error in judgement could mean catastrophe and/or death. People worked hard from sun up to sun down.

It struck me, ironically, as I lay on the beach reading and not working hard at all, how much Ma Ingalls did in a day. She made three meals a day over a fire/woodstove, she aired the beds, made the beds, washed dishes in a tub by hand, took care of three little children, and then did the big jobs--one per day of the week except Sunday. As the book says,

Wash on Monday

Iron on Tuesday

Mend on Wednesday

Churn on Thursday

Clean on Friday

Bake on Saturday

Rest on Sunday

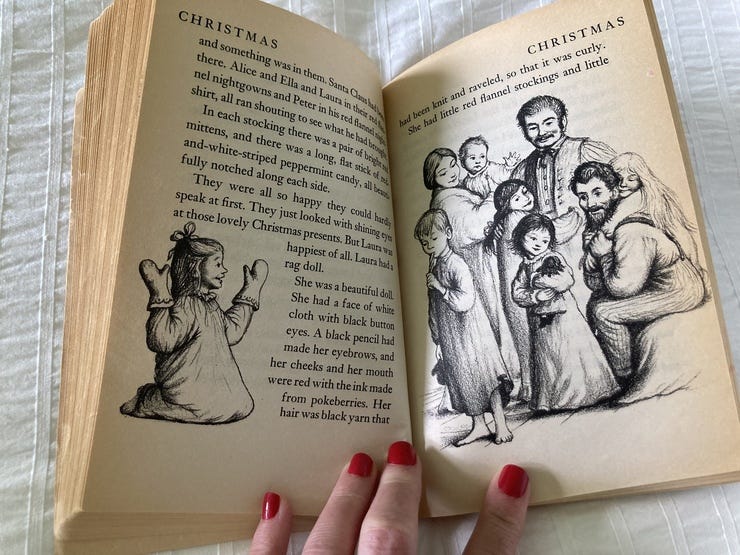

She scrubbed the clothes clean by hand, rinsed them, wrung them and hung them out to dry. The next day, she heated the irons on the stove--just right. Too hot, they'd burn. Too cool, they wouldn't iron. She made butter in a churn on Thursday. She cleaned the house on Friday with a broom, a bucket and scrub brush. She baked the family's bread, cornbread, cookies and pies on Saturday. You would think from all that work and bother, Ma would have been a severe woman with not much tolerance for nonsense and frippery. But on the contrary, she was warm, soft, kind and pleasant...and inclined to get all gooey eyed over pretty things. Over and over again, I saw the hints of this.

In winter the cream was not yellow as it was in summer, and butter churned from it was white and not so pretty. Ma liked everything on her table to be pretty, so in wintertime she colored the butter.

And she didn't seem to think it beneath her or a waste of her time to go to extra work and bother to make things pretty. Coloring the butter, then putting it into a pretty mold was a time-consuming process, but she did it anyway. Go get the book and read about it. But that wasn't the only example.

The lamp was bright and shiny. There was salt in the bottom of its glass bowl with the kerosene, to keep the kerosene from exploding, and there were bits of red flannel among the salt to make it pretty.

And not just Ma...

Every night [Pa] was busy, working on a large pile of board and two small pieces. He whittled them with his knife, he rubbed them with sandpaper and with the palm of his hand...Then with his sharp jack knife...He cut little holes through the wood. He cut the holes in the shapes of windows, and little stars, and crescent moons, and circles. All around them he carved tiny leaves, and flowers and birds.

All this effort every night after a day of manual labor, just to make a pretty shelf for his wife so she could put her pretty china figurine on it for display. And for what purpose? It didn't feed them, or clothe them, tidy up, declutter, or make income. All these examples were of ordinary humans making something beautiful for beauty's sake.

I'm not sure that there is a moral to all of this, other than the fact that people who worked much harder than I ever have, who knew more practical skills than I'll ever have...thought that making things pretty just because was worthwhile. And perhaps I shouldn't feel so silly that I get a genuine thrill of happiness by making things pretty just because, too.

I suspect that God made us to be that way. Because there are some things in nature that don't have to be pretty to function that aren pretty. I think God made them pretty, just because.

And so, friends, go forth and make things pretty.

Until next time, folks.